We live in the age of high tech. High technology. So common, so ubiquitous, that we almost take it for granted. This morning most of us got up and grabbed hold of a small device that has more computing power than that which landed a man on the moon. We’re hardly alone. Did you know, that over four-and-a-half billion people – more than half the humans living on the planet – own and use a cell phone?

The cell phone became commercially available in 1983. Thirty-two years later, half the planet uses one. At that trajectory, by the year 2047, every man, woman and child could be connected to every other human via microwave link. That’s a pretty fast rate of adoption.

Mid-range technologies – let’s call them “mid tech” – aren’t as “sexy”, and often take a little longer to catch on. The Edison Electric Light Company introduced commercial electric lighting to homes and businesses in 1878; today, 20% of the world’s households (1.3 billion) do not have electricity. At that trajectory, every home in the world could have electric lights and refrigeration and cell phone chargers by the year 2042.

But here’s an interesting example of the very slow crawl of “low tech.” The earliest example of a house chimney, a structural device designed to draw smoke and gases from the interior of a dwelling to the outside air, occurred in England in the year 1185. Eight hundred and thirty years later, there are an estimated three billion people who live in homes that rely on cooking and heating from open fires on the floor, unvented to the outside. At that trajectory of adoption, we can expect to vent smoke out of everyone’s homes by year 2356.

Let’s put this into perspective. In less than a lifetime, we will place Facebook, Angry Birds, streaming music, and sexting into the hands of everyone. But it could take us an additional three-and-a-half centuries from today to remove the greatest environmental cause of disease and death, and the third greatest contributor to global climate change, faced by that same population.

The iPhone 6s retails, without contract, for $849; a simple, vented woodburning stove costs ECOLIFE about $100, parts and labor. If we follow the average, our phone will last less than two years before we upgrade to a new one; the stove will last eight years.

The stove, by its design, reduces the amount of wood required to fuel a common, three-stone indoor fire by 70%. That’s 70% less of this (pictures of wood being carried and stripped forest), and approximately ten fewer hours per week spent – mostly by women and children – gathering that wood. Can you imagine what a child might do with ten more hours a week? Maybe go to school. Can you imagine what a woman might do with ten more hours? Maybe start a business.

The stove, multiplied by the number of homes on this planet that need one, will save a gigaton – that’s a billion tons — of greenhouse gases from spewing into our atmosphere every year – that would be like taking every motor vehicle in the United States off the road… plus Canada… plus Mexico… plus China… plus India… okay, basically a third of the cars, trucks, buses and tractors on the planet.

The stove, in every home where today burns a fire in the middle of the floor, will prevent an estimated 4.3 million premature deaths each year from smoke-related diseases, and countless painful, disfiguring and often fatal burns to children who fall into fires.

With your smart phone, however, you can book a restaurant, check on your stocks, and take of selfie of yourself to let all your friends know that you’ve got nothing better to do.

Over 500 million stoves are needed, today, in the developing world. That’s a daunting task. First of all, how much would that cost? According to the calculator on your smart phone… five hundred million, times $100 per stove…why, that’s $50 billion dollars. That’s a lot of money! That’s almost as much as Apple earned in the last quarter! ($51.5 billion). That’s almost as much as we’ll spend on our military presence in Afghanistan next year… where we have ceased all fighting by U.S. troops ($62 billion). It is nearly the amount we Americans spend on our pets ($61 billion), soft drinks ($65 billion), and playing golf ($69 billion) each year.

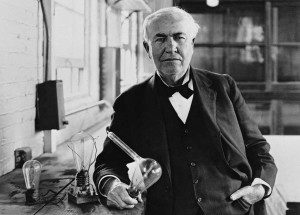

So let’s say somebody wrote us a check for $50 billion… how would we build all those stoves? General Creighton Abrams coined the famous phrase, “When eating an elephant, take one bite at a time.” ECOLIFE has built over 1,500 stoves in Uganda, Kenya and Mexico. That’s a bite. But we’ve seen how technology spreads, how it mushrooms from one happy homeowner to her neighbors, and from a neighborhood to a village, and from one village to many others. Steve Jobs and Thomas Edison both knew: Create the demand, and the market will respond. This is an 830-year-old solution whose time has come!

I spent 20 years with the San Diego Zoo, communicating the importance of wildlife conservation. And a constant frustration for me there was how we would tell Zoo visitors that this animal and that animal were on the brink of extinction… and after completely bumming them out about how their grandchildren might never see a live rhino or panda or leopard, we would offer our audience no tangible way for them to help avert these tragedies. Nothing that they could do… except to go home and lose sleep over it.

Did I mention that our stove projects in Mexico surround the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a World Heritage Site endangered by deforestation – much of it in the name of fuel wood gathering? Did I mention that our stove projects in Uganda is in the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, home to half the world’s endangered mountain gorillas? Or that our stove projects in Kenya are in the Serengeti, where human activity impacts the survival of black rhinos, cheetahs… and elephants?

Most plants and animals on today’s Endangered Species list are there because they’ve lost their habitats… like their forests. Fuel-efficient stoves help to preserve those forests. It’s like everybody wins.

This is a lot to think about, I know. Phones and lights and stoves and smoke and disease and burns and the empowerment of women and the price of a round of golf. And how to eat an elephant, and how to save an elephant. But there’s really just one simple takeaway here.

The science fiction writer William Gibson, often considered a “prophet” of sorts because his books seemed to forecast trends and technologies, shook off that label by saying that “The future is already here… it’s just not evenly distributed yet.”

We have a big problem with a low tech solution that’s been around since the twelfth century. It’s high time that we complete its distribution.