When Orange Clouds Fly Thin

Written by Jackie Bookstein, ECOLIFE Intern

There are many natural phenomena around the world that have become beloved traditions to local nature admirers. For many San Diegans, it is the grunion run that happens at the full and new moon every summer. For me, it was the adventure into our deserts to see the rainbow explosion of flowering plants for those few weeks in the spring. All over the Unites States, locals fondly recall the brilliant display of fiery wings, as streams of monarch butterflies migrate between their summer and winter homes.

Unlike other butterfly species, monarchs do not overwinter in our cold northern climates. Perhaps a reason they are the most iconic butterfly in North America, monarch butterflies are the only butterfly that make an epic, round trip migration for the changing seasons. There are many species of migratory birds that fly similar journeys, but there is an astounding element to the monarch migration that is unlike that of the birds.

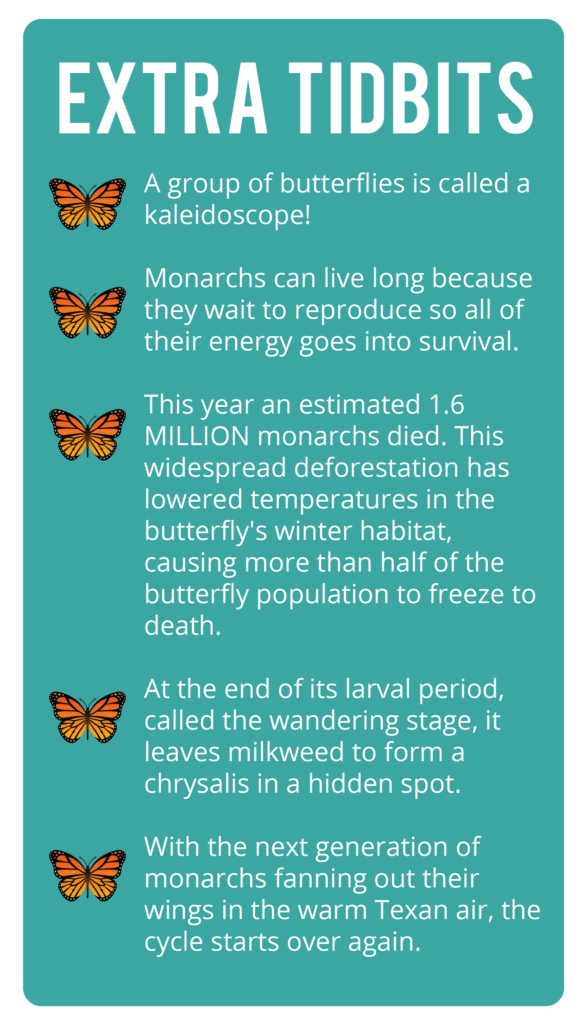

Butterflies live much shorter lives than birds. For three generations in a row, a monarch butterfly will live only four to six weeks as an adult. Each generation contributes to a leg of the journey, some flying west to the coast of California, some south to the mountains of central Mexico, depending on the population. But the fourth generation that emerges in late summer, called the Methuselah generation, will live seven to nine months after coming to maturity, by far covering the longest portion of this journey.

In eastern populations, this fourth generation often travels up to three thousand miles to spend the winter in the Oyamel forests of Mexico. In February and March, they become active again in preparation for the journey back north. Weary from their voyage south and the long months spent in the Oyamel forests, this generation only makes it back as far as Texas, where they lay their eggs for the next generation before finally dying. It will take at least three more generations of monarchs to reach the northernmost part of their journey, the Canadian border, to prepare for the laying of their Methuselah generation, thus starting the cycle all over again.

Unlike migratory birds, every single individual butterfly is making the journey for the first time. The monarchs starting out on their winter journey are at least three generations removed from the generation that made the return journey earlier that year. For years, scientists couldn’t pin point the navigational strategies that make this possible, but recent findings have finally brought some clarity. Researchers identified a combination of two mechanisms that contribute to this unique ability: a capacity of the eyes to track the position of the sun and a timekeeping mechanism in the antenna. Together, these signals lead the monarchs to the exact same patch of forest, arriving on the exact same day each year.

Every year we see less of these delicate droves of fluttering orange. Their populations now stand at less than 20% of the historical average. This immense decrease is primarily attributed to habitat destruction and agricultural practices that have led to the loss of milkweed throughout North America. A monarch butterfly lives out the first two stages of its life, from egg to larva, only on this one type of plant. With the eradication of milkweed plants, the monarch has nowhere to reproduce.

Those that are able to reproduce into the Methuselah generation are also in trouble. Each year a hundred thousand trees are cut for fuel around and within Central Mexico’s Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR) in Michoacán province. The degradation of the forest limits its ability to buffer against big swings in temperature. Without this buffer, sudden temperature drops have caused three mass die offs in the last sixteen years, the worst of which caused the deaths of tens of millions of butterflies in one night.

It isn’t only for nostalgic reasons that people all over the country are pushing to protect the monarchs. The butterfly plays a major role in our country’s ecosystem as an important pollinator species. As both prey and predator, they are also a principal part of their food cycle, and a major indicator species. This means we can make inferences about the current state of our environmental health by observing the monarch. Right now, our observations point to pretty dismal speculations. It is for these reasons, as well as the nostalgic affection for North America’s most iconic butterfly, that the people of ECOLIFE are trying their hardest to keep these critters alive and flourishing.

ECOLIFE is addressing both local and international problems by encouraging people to plant native milkweed and working with communities around the Oyamel forests in Mexico. The program provides indigenous populations with more efficient wood-burning stoves for cooking and heating their homes. These “Patsari” stoves are 60% more fuel-efficient than cooking over the traditional open fire. The use of these stoves means fewer trees destroyed, as well as significantly less respiratory ailments and hazardous smoke emissions to Michoacán residents. Since 2004, ECOLIFE has built over a thousand permanent, vented, safe, fuel-efficient stoves in areas that impact the butterfly reserves and surrounding forests.

During down time of my internship here at ECOLIFE, I gather around a big table with other interns to stuff little bags of milkweed seeds that will be handed out to the public. With each bag of twenty seeds, I can feel the life of twenty blooming milkweed plants, and from them the homes of forty munching caterpillars who will soon become the billowing clouds of tiny creatures I use to watch in wonder as a child. If every one of these seeds that passes through my hands actually gets put in the ground, our autumn skies could possibly come to life the way they once did just a few decades ago.

To learn more about ECOLIFE’s Mexico Stove Program, please visit our website.